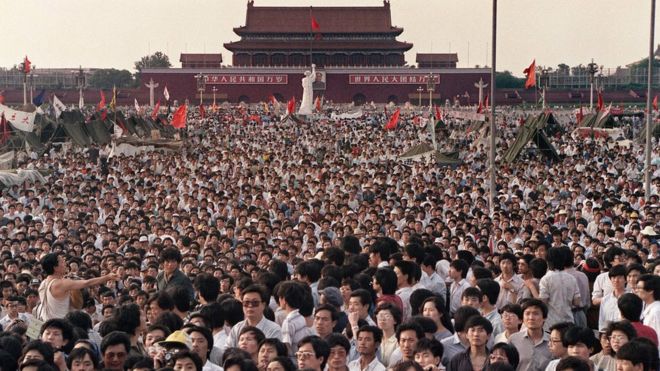

June 4, 2019 represents the 30 year anniversary of the Tiananmen

Square massacre.

I was always led to

believe it was a gathering of students from universities around the country to

demand democracy. The communists that run that country got fed up and ordered

the Army to roll into the square and start shooting. That’s an oversimplification

but close to the mark. The protests began with students but brought in people

from all over the country and held in other cities, not just Beijing. The

demonstrations began after the death of a popular reformer named Hu Yaobang.

They quickly evolved into a genuine call for democratic change with a list of demands that

students wrote up. Hu Yaobang died in April and the troops marched on the city

in June.

The students pushed for greater openness but the movement

was disorganized lacking unified aims and leadership. Initially some demanded

to speak to the premier (Li Peng). When he didn’t show they began a hunger

strike. Protesters were selected at random to carry messages to government

officials. Often they were ignored or patronized. A famous editorial circulated

in the People’s Daily (the official

news outlet) that called the movement “anti-government” and hinted that the

students were guilty of insurrection. It was a clumsy move that angered more of the

Chinese and increased support for the students. No one thought it was

anti-government to want a voice in the future of the country. Even if the

cluttered mass of people spilling on the square had different ideas about reform,

no one argued to overthrow the Communist party.

I get the sense that the protest was too big to be unified.

It was never clear throughout the 6 weeks who was in charge, who were officials

supposed to talk to? Only one of the demands had to do with democracy: “Affirm

Hu Yaobang’s views on democracy and freedom as correct”. Another demand wanted

higher pay for ‘intellectuals’. They

demanded press freedom. They wanted salaries of communist party official made

public. Nothing is wrong with any of these demands. But the party officials

were growing tired of month long protests, demonstrations, hunger strikes and

emotional calls for this or that.

It’s impossible to

really know what the communist party leaders were thinking behind the scenes. It’s

not like they hold press conferences. They keep a tight lid on internal strife

and power politics. Officials don’t leave the politburo and write tell all

books exposing dirty laundry of their enemies. It helps to understand that the

leadership operates through factions. Alliances form because of loyalty among individuals. Similar to an American company CEOs like to work with those they’ve

worked with before, who can be trusted. But alliances also form along

ideological lines. Unlike corporate America the loosing factions don’t face

show trials for corruption on national TV.

The stakes are very high.

Alliances led by Deng Xiaoping wanted a swift end to the

demonstrations at Tiananmen without giving up anything. A high level meeting

with the visiting Gorbachev was moved to the airport since the students

occupied the square. This embarrassed Deng no doubt. Alliances that were

sympathetic to the protesters were led by Zhao Ziyang (General Secretary). He was against calling

for martial law but lost the battle to the enforcers like Jiang Zemin. This

conflict eventually led to a purge of

reformers like Zhao after the Army rolled into Beijing and killed a lot of what

remained of the demonstrations.

No one knows exactly how many were killed but estimates

range from a few hundred to a few thousand. It’s hard to get numbers from a

party that tries harder to deny the existence of the massacre. Not that they

really know anyway.

Most foreigners recognize June 4, 1989 as the day China

turned the Army on its own people.

Chinese censors try every year at this time to erase the

memory of the brutal crackdown. They block websites that mention anything in

relation to the day the tanks rolled. The international condemnation was swift.

The Communist government lost a lot of foreign investment it desperately

needed. So what lessons were learned by students, citizens and democracy

advocates? How did the party change after this?

Crackdowns are swift and brutal. From illegal churches to online dissenters,

the long arm of the state moves quickly. The government allows protests and

even radical demonstrations, as long as the victims are foreign embassies or

foreign companies. In this way the angry ‘masses’ are allowed to vent

frustration without challenging the legitimacy of the CCP. An inherent trade-off

exists on the mainland, prosperity for compliance. As long as China keeps its

population working and its economy growing they won’t bother with this

democratic ‘silliness’. So far the structure has held together well enough,

longer than a lot of foreigner observers thought. But no one really knows when

a spark could ignite another round of rebellion.